‘And the Silicon Heartland Begins’: How Intel Is Betting Its Future on Ohio

Amid rising demands for semiconductor chips and a domestic semiconductor supply chain, Intel is making a historic investment in New Albany, Ohio to build the company’s first manufacturing site in 40 years — and potentially one of the biggest chipmaking factories in the world.

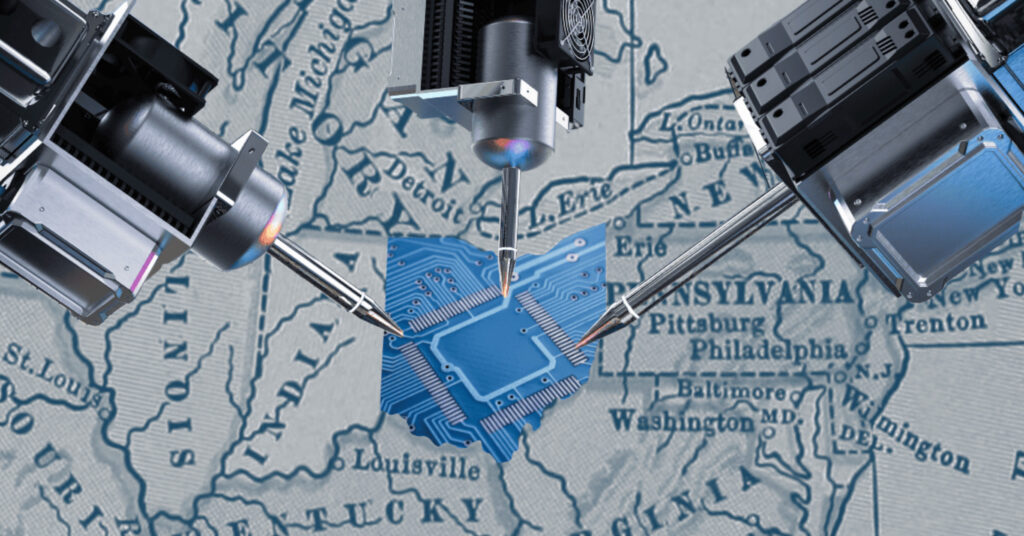

Cover graphic by Casey He.

Electrical engineer Jack Kilby invented the integrated circuit, or chip — a piece of semiconductor that contains various electronic components — in 1958 while working at Texas Instruments. Several years later, a group of integrated circuit pioneers founded a small company in California. Taking the initial letters from integrated electronics, they named their new venture Intel.

More than six decades later, as one of the world’s preeminent chipmakers battling to regain ground in the semiconductor manufacturing business, Intel is making an ambitious bet. The company is trying to bring its first manufacturing site in 40 years to a state that, unlike California or Texas, is not known for producing the tiny chips at a massive scale.

In January 2022, Intel announced that it had selected New Albany, Ohio, a suburb east of Columbus as the site for two semiconductor fabrication plants, or fabs. The company said it would invest $28 billion into the facility, which is expected to create 3,000 jobs. The campus is now slated to be finished in late 2026, according to reporting from The Wall Street Journal.

As the company prepares to slash more than 15,000 jobs worldwide as a part of a $10 billion cost-cutting plan in response to disappointing second quarter earnings, Intel said its plan for Ohio will not be affected.

“The Rust Belt is dead, and the Silicon Heartland begins,” Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger said at the September 2022 groundbreaker for the New Albany facility, touting that it would produce the world’s most advanced semiconductor technology and help the U.S. “regain its manufacturing heart as well as unquestioned technology leadership.”

Since the semiconductor’s invention, the U.S. had been a leader in its development and manufacturing. But, as chip complexity and costs of manufacturing equipment rose, many American companies moved toward the “fabless model” — outsourcing production to specialized manufacturers known as foundries — Willy Shih, a professor who specializes in technology and manufacturing at Harvard Business School, said.

America’s Share of Chip Manufacturing Capacity Has Seen Serious Declines in Recent Decades

The COVID-19 pandemic, however, exposed the fragility of a supply chain that revolves around a few manufacturing sites, as factory closures caused severe chip shortages and delays across industries. Heightening tensions between Taiwan and China have also sparked concerns about continued American reliance on a “geologically and geopolitically unstable region” for advanced chips, Shih said.

These concerns have been the driving force behind a national strategy, in which Intel’s project is a centerpiece, to bolster semiconductor manufacturing in the U.S. and establish a robust domestic supply chain for chips. The CHIPS and Science Act, which President Joe Biden signed into law in 2022, aims to siphon $50 billion into the American semiconductor industry, one of the largest federal investments in one industry in decades.

In March 2024, the Biden administration announced the largest of the incentive packages under the CHIPS Act to date — $8.5 billion in grant money and up to $11 billion in loans — will go to Intel. The funding will go to four states: the company’s manufacturing facilities in Ohio, Arizona and New Mexico, as well as its research and development hub in Oregon.

“It’s going to transform the semiconductor industry,” Biden said of the package at a March ceremony at the Intel campus in Chandler, Arizona. “Where the hell is it written saying that we’re not going to be the manufacturing capital of the world again?”

Forty states competed for the project Intel envisioned — a 1,000-acre campus with the capacity to host the initial two and up to eight fabs — according to Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine. But it was Ohio that came out on top.

To Kenny McDonald, president and CEO of Columbus Partnership, a group of over 75 chief executives of area businesses and institutions, the site selection highlights the potential of the Columbus region.

The New Albany International Business Park, which the Intel facility would be a part of, has already attracted a slate of manufacturers and high-tech businesses like Google and Meta for their data centers, McDonald said. The area also has robust infrastructure, especially a strong water supply, which is crucial to the water-intensive semiconductor manufacturing process.

“We believe that we have the raw material, if you will, not only to construct one of the most complicated facilities in the world, but then populate that with both the technical expertise and the engineering expertise that a project like this requires,” he said.

Another aspect of Columbus’s winning pitch was the area’s educational institutions and their potential for collaborative workforce development with the semiconductor industry, Scot McLemore, the executive in residence at Columbus State Community College, said.

To invest in workforce development in the state, Intel has committed $50 million to Ohio’s higher education institutions. McLemore said Columbus State, a recipient of the grant, worked directly with Intel to design new courses, including one on the fundamentals of semiconductors and another on vacuum systems, which are commonly used during the chip manufacturing process.

While Intel is betting on Ohio to host the future “epicenter for advanced chipmaking” and potentially one of the largest semiconductor manufacturing sites in the world, local leaders agree that the project has the potential to transform the Columbus area. Intel is estimated to create a combined 20,000 jobs — both at the facility and at area suppliers and supporting businesses — and add $2.8 billion to Ohio’s annual gross state product, according to the Ohio Governor’s Office.

Intel will further diversify the Columbus area’s economy, which already features strong manufacturing, financial services and logistics industries, McDonald said. While the industrial decline of the 2000s left Columbus less scarred than some other Midwestern locales, the metropolitan area lost 40,000 of 105,000 jobs in the manufacturing sector between 2000 and 2010, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

McLemore said Intel’s investment will help strengthen collaboration between Ohio’s two- and four-year colleges in sharing resources to help feed graduates into the new, diverse job opportunities, including many that would not require a four-year degree. He said Columbus State plans to quadruple the number of students it trains in engineering technology over the next five years.

“As someone who made their career in advanced manufacturing … I think it’s a wonderful opportunity for communities,” McLemore, a former executive at American Honda Motor Company, said. “I think, however, the challenge is making sure that everyone in the community has an opportunity to be a part of it. It’s a real chance to impact those that have been historically left behind with these types of opportunities.”

But some local residents have raised concerns over the environmental and health impacts of the chipmaking facility. Intel is expected to use 5 million gallons of water per day, making it the largest water user in Columbus. Residents also worry the factory could release toxic chemicals into the air or the water supply, causing health issues among workers and the site’s neighbors.

Madhumita Dutta, a human geography professor at the Ohio State University specializing in economy and labor, said that following the Intel project’s announcement, there has been an abundance of talk about its economic benefits, but not enough conversations about its impact on the environment, sustainability and health.

“Because you build a particular kind of expectation, you build a particular kind of narrative, one has to — at this time — ask some hard questions, so that both the corporation and the state are held accountable, because ultimately, these are taxpayers’ money. This is the environment we’re talking about. We’re talking about health,” Dutta said.

For Intel to receive incentives from Ohio, the company is required to file an annual report on the New Albany facility. While Intel released its 2023 report in March 2024, Dutta said it contained little information on the environment and health aspects of the project. The company and government agencies have also been reluctant to release relevant information, such as the types of chemicals that would be discharged and their mitigation, citing trade secret protection.

To ensure environment and public health considerations, as well as those on equity and labor protections, are central to semiconductor projects around the country, Dutta became a member of CHIPS Communities United, she said. A coalition of researchers, advocates, health professionals and trade unions, the group was established to ensure “the responsible and equitable implementation” of the CHIPS Act and its disbursement of government investments.

While some have argued that the Biden administration has used the CHIPS Act funding to pursue political advantages — a significant portion of the CHIPS Act investments is set to go to Arizona, a state of much importance to the Democrats’ fortunes in the upcoming presidential election — the New Albany project has won bipartisan support across Ohio.

Matt Dole, the chair of the Republican Party in Licking County, which encompasses the Intel site, said he is fascinated by the project and the positive impact it would bring to the community.

“The construction — and certainly a $20 billion investment — just blows the record off economic development programs. It’s good for schools. It’s good for the local communities … It’s certainly good for the state and good for the nation that we get to play this outsize role,” Dole said. “So I think it’s good politics and good economic development.”

Although the U.S. has made significant investments in onshore semiconductor manufacturing, Shih said he doesn’t see the semiconductor industry moving away from being a “global effort,” and the success of Intel’s semiconductor manufacturing hub in Ohio will depend on industry conditions.

“When you do a greenfield site like that, that’s a long term bet,” he said. “That’s not for the faint of heart.”

Nonetheless, McDonald remains optimistic about the project and what it means for the Columbus area and the surrounding region.

“It shows that anything’s possible in the Midwest, and that we have all the resources and capability of any part of the world,” he said. “I hope it actually increases the ambition of everybody across the Midwest. It’s certainly done that here in the Columbus market.”

SOURCE: https://www.midstory.org/and-the-silicon-heartland-begins-how-intel-is-betting-its-future-on-ohio/